The Catalogue Raisonné: An Art Collector's Underutilized Friend

Catalogues raisonnés are an incredibly valuable resource for art lovers building a collection, but their utility remains relatively unknown to the general public. This is due in part to confusion over their French name, catalogue raisonné, which translates roughly to “reasoned catalog” in English. So what is a catalogue raisonné and why is it important?

A catalogue raisonné is an official documentary record gathering all known artworks attributed to a specific artist and publishing them together with illustrations of each and information about the history, provenance, and attribution support for each work (which is where the “reasoned” part in the French phrase comes from as the reason the art is attributed is included for each piece). A catalogue raisonné for an artist is traditionally prepared by the art historian who is the recognized authority on the work of that particular artist, or by a team of art historians who are all specialists in the work of the artist.

The process of generating a catalogue raisonné takes years to complete and involves painstaking research to sort out artworks that truly were created by the artist from works that were created spuriously to deceive or were perhaps created instead by an apprentice or contemporary with a similar hand. Inclusion within a catalogue raisonné is the ultimate statement about the artwork’s authenticity, and the absence of a work in an artist’s catalogue raisonné raises serious questions about whether it is a forgery (click here to read about this topic).

The professional fine art community has consulted these resources for decades as part of authentication research, but increasingly as the art market expands and online sales directly to consumers increase, catalogues raisonnés are critical tools for art collectors to be aware of as well. If you are considering a future purchase of an artwork signed for a particular artist but are not sure if it is authentic or hope to build a collection of several pieces by the same artist over time, then I encourage becoming familiar with the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It is very important for ensuring that you are not being taken advantage of through purchase of a spurious work.

Where should a collector begin? First of all, it helps to know what a catalogue raisonné usually looks like and how to locate one. Traditionally, catalogues raisonnés were published as physical books, often very thick and filled with illustrations of each artwork. One artist might have multiple catalogues raisonnés created for each medium she or he worked in, such as a volume for oil paintings, a volume for drawings, and a volume for etchings. In the last few years, a number of catalogues raisonnés have been created that are instead posted online as a website, such as the Isamu Noguchi catalogue raisonné which allows much greater flexibility to update in the future if new artworks are discovered and authenticated for inclusion.

This brings up the point that it is very important to pay attention to the date the catalogue raisonné was published, as they are often updated through the years with new expanded editions being released. If you are consulting an out-of-date catalogue raisonné you may miss out on important new scholarship.

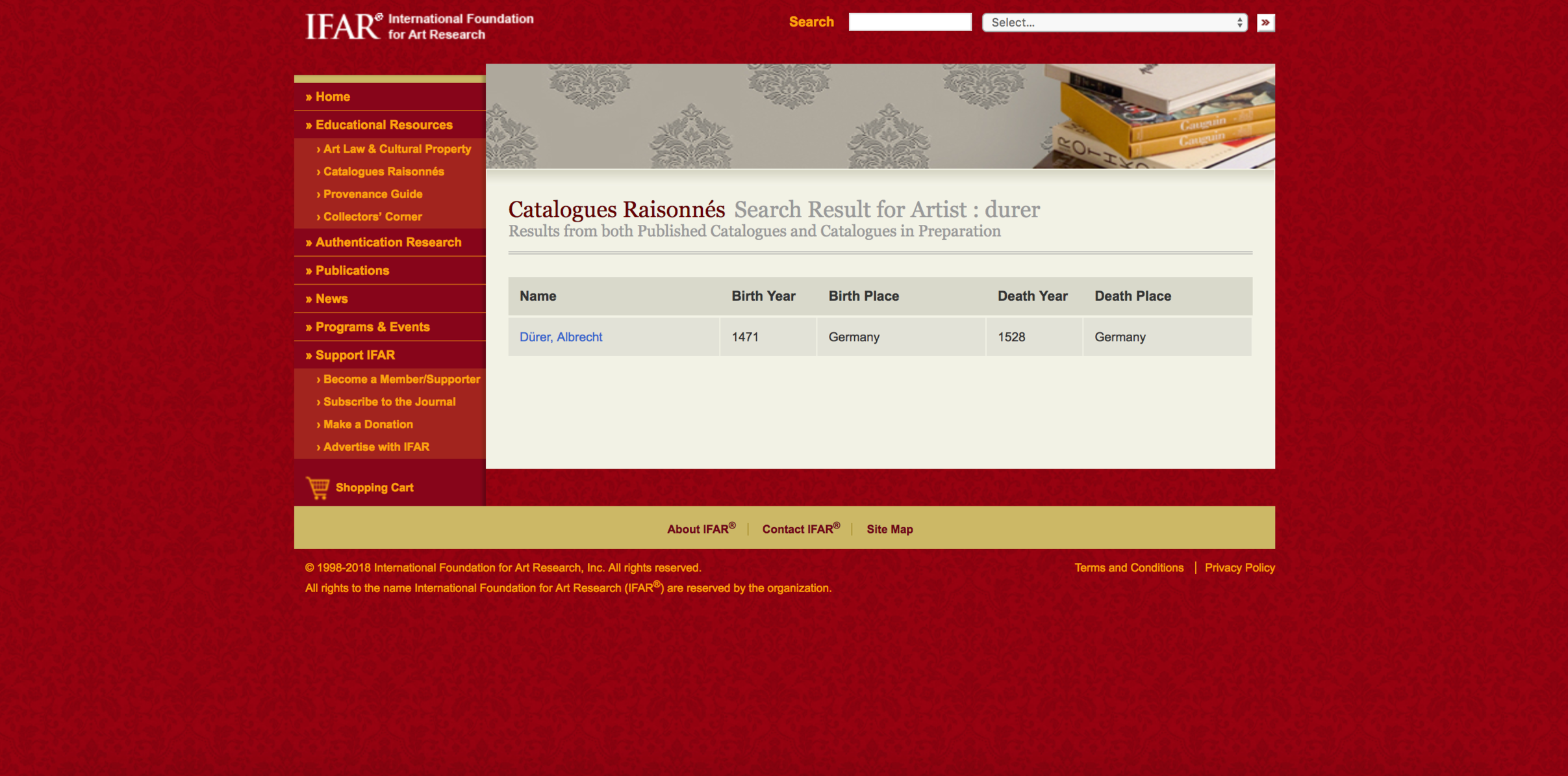

The best way to locate the catalogue raisonné for an artist and identify which edition is the most recent is to consult the website of the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) which maintains a comprehensive searchable database of catalogues raisonnés. [Author Update: This article was originally published in August 2018. On September 27, 2024, IFAR announced that it would be shutting down and rehoming its assets including the catalogues raisonnés database with other organizations. This article will be updated with links to the database’s new home once that information becomes available.]

IFAR lets you search both for published catalogues and catalogues in preparation, which is useful to identify who to contact if a published catalogue raisonné does not yet exist for your artist. The search results also include all works published for the artist and their dates of publication so you can easily sort for the most recent publication. Not every artist has a catalogue raisonné yet in existence, and the artists who don’t are ones to be especially careful about when considering a planned purchase, as the portfolios of these artists are more attractive for forgers as it is harder to document if something is wrong without a catalogue raisonné. Fortunately, many artists do have catalogues raisonnés, such as Albrecht Dürer, who had many catalogues raisonnés published about his art over many decades. A search for “Durer” in the database brings up the following screen:

When his name in blue is selected, the listing of all of the works published about his portfolio and their complete publication information appears.

From these results, you can easily see that they are sorted by date with the most recent publications first, and clearly identified by medium so you can select which one matches your work.

The next challenge is once you have the title you need to identify, how do you find it? This is a little trickier. Since they are such huge books full of illustrations and taking many years to prepare, catalogues raisonnés are usually very, very expensive to purchase. Few individuals, even in the fine art field, actually buy copies of catalogues raisonnés, but instead consult them in the collections of fine art libraries. If you live near a large university or near a city that has an art museum with a reference library, there is a good chance they would have the volume you need in their holdings. If not, many appraisers offer catalogue raisonné research as part of their paid service offerings.

Once you’ve used the IFAR database to determine which catalogue raisonné to consult, the next step is to consult another free database, which is called Worldcat. Worldcat lets you search for books across libraries throughout the world and the results are arranged in the order of physical proximity to your location. As an example, if I was looking to find a copy of Van Gogh: The Complete Paintings, written by Ingo Walther and Rainer Metzger in 2015 I would search in Worldcat and enter a zip code (I’ve entered 20001, which is the zip code for the north east section Washington DC). I receive the results for the book, including where I could buy it online (this is happily one of those few catalogues raisonnés that can be purchased inexpensively), as well as a listing of libraries near the zip code 20001 where the book could be consulted in person.

From there I could select the library most convenient to me and go consult the book. I can’t say I’ve ever had the occasion to check out the Van Gogh catalogue raisonné to see if an appraised painting is included in it, but that would certainly be an interesting assignment!

Now that you’ve been able to get your hands on the volume you need, how do you use it? Many catalogues raisonnés are not written in English, so it can be even more challenging to search if the artwork you are considering is included in a text you can’t decipher. This is where the illustrations are exceedingly useful and it is also a helpful guide that many volumes are arranged chronologically. If you know the date the work you are looking for was supposed to be created, that can be a good way to pinpoint your research. Speaking from my own practices, I generally go through every single page in the book carefully anyway because I want to confirm that I haven’t missed anything.

At this point, you will likely encounter one of two options. Either you will find your work included, or you won’t. If you do find your work included, that’s probably pretty good news, but make sure to study all the details very carefully to confirm that it is in fact your work. One downside to catalogues raisonnés is the detailed illustrations are great resources for forgers as well to copy from. Another key detail to pay attention to is where is the work currently located, which is a standard part of each entry. If the catalogue raisonné says it is presently part of a museum collection, you have a big problem. Sometimes you might find your work listed with an old photograph with “location unknown,” at which point I strongly recommend contacting the writers of the catalogue raisonné to submit photos of the work and obtain their opinion. Artworks do resurface all the time, and it can dramatically add to the value of the work to have it officially recognized by the catalogue raisonné and included in future updates of the publication. Artwork that disappeared in Europe during World War II is another potential problem to be aware of, as many of these works have unfortunate associations with seizure by the Nazis, and the title of the art may still be in dispute. If it is a work you already own rather than a planned purchase and the catalogue raisonné specialists request physical custody of the work to inspect, it’s very important to determine in advance what will happen to the art if they decide it is not authentic. There have been a number of highly controversial cases in France where artworks were destroyed by the committee rather than being returned to the owners after they were declared “not right.”

If you don’t find the work included in the catalogue raisonné, this is generally not promising news, but sometimes there can still be a positive outcome. I’ve worked with paintings that were not included in a catalogue raisonné that were accepted and added. In these situations the works had a great documentary provenance that fully checked out the chain of descent, and they’d simply fallen off the radar so long ago that the catalogue raisonné team had no photographs or documentary evidence other than family oral history to support its existence until the works resurfaced. If you have a strong provenance or documentary support, it can be well worth reaching out to the catalogue raisonné team for their opinion. As a side note, this is a good place to correct the common assumption that appraisers are also authenticators, which is something I get a lot of calls about. In this assignment I didn’t authenticate the painting but rather worked with the catalogue raisonné team, who served in the official authenticating role. Appraisers are not authenticators even though they are frequently assumed to be—they work with authenticators as consultants when authentication is needed.

The printed books usually don’t provide contact information about how to reach the catalogue raisonné team but what I like to do is search for the names of the authors. As noted art historians, many have an institutional posting at a university, and I can use their university contact information to write to them. If the work is instead a planned future purchase that you have an uneasy feeling about, its absence in the artist’s catalogue raisonné can help you decide to pass on adding the piece to your collection. Inclusion in a catalogue raisonné is a major value attribute. From an investment perspective you should be cognizant of the potential difficulties you might encounter if you wish to sell the artwork in the future, and it is not included in the official catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work. If it is a piece you will enjoy living with and it’s at a cheap price and you don’t care about attribution, then by all means go ahead and purchase it and enjoy it for its decorative appeal. But for collectors looking to build a group of authentic artworks that have the potential to appreciate over time, I strongly encourage you to become familiar with the catalogues raisonnés of the artists you are most interested in.

As a final point (and this is where my inner art nerd is really showing), catalogues raisonnés can be very fun to read. They are a great way for visually studying an artist’s evolution of style over time and discerning which eras of creativity you are most attracted to. Studying the illustrations together with the supportive text brings an added understanding of how the artist’s life experience shaped her or his work and helps you develop a more nuanced appreciation for the art so it can bring even more joy to your daily life.

Sarah Reeder, ISA CAPP is Co-Editor of Worthwhile Magazine and owner of Artifactual History® Appraisal. She is also the creator of the online course SILVER 101: Quickly Learn How to Identify Your Sterling Silver and Silverplate to Find the Valuable Pieces and Sort with Empowered Confidence, available on-demand at https://artifactualhistory.teachable.com/p/silver-101. Sarah can be reached at her firm at https://www.artifactualhistory.com/