A Brief Guide to Handling Ivory Material in Client Collections

Today, government regulations have left ivory with a diminishing market, and in some cases, no market for the purpose of determining fair market value. But, there are instances where ivory can still be sold. Ivory has been used from ancient cultures to the present day, resulting in a lot of fine and decorative works of art made or inclusive of ivory in collections.

As an appraiser, you need to know how to advise your client about appraisals and the possibility of sale for their items containing or made of ivory. When approached with a question about ivory, there are a few questions you should ask.

Is it ivory or bone?

Ivory is usually indicated by a lack of bone marrow. Ivory, or tusk, is technically tooth material meaning it lacks the channels to carry marrow. Bone has small cavities for the transmission of blood and nerves.

In contrast, Elephant ivory is identifiable by Schreger Lines: a series of patterned lines reflecting the increasing size of the tusk. Elephant ivory is different from marine ivory and different from other types of ivory. But, as it is the subject of most regulation, it is the primary example I will use here.

If you really can’t tell exactly what the piece is made of, reach out to an expert. Many appraisers can tell the difference with a quick inspection, particularly in fields with a history of ivory workmanship, such as in Asian Works of Art.

The regulations on bone, particularly worked or carved bone, are generally much less strict than for ivory. DNA testing is generally required to determine the type of animal bone, but the likelihood that it belongs to an endangered species is rare. For this reason, it is difficult to regulate the sale of bone, and most objects made of or incorporating bone that have artistic merit or historic interest, will be able to be offered for sale in most states.

For bone or other materials taken from an endangered species – elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, etc. – the likelihood that a market exists, one that is not illegal or underground, is very low.

If you determine the piece to be ivory, the next question to ask is…

Bone (unidentified) as seen through a loupe.

Source: Richelle Simon, ISA

Ivory (Elephant) close up image with Schreger lines.

Source: Richelle Simon, ISA

Is this worked or unworked?

These are terms often used by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Worked” implies the object is carved, sculpted, or otherwise made into art. “Unworked” means the object is a whole or partial tusk.

There is a very limited market for unworked elephant tusks. These items are restricted for export commercially, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife regulations. Domestic sales of whole-tusks are possible in some circumstances, but the market is very small and carries a negative social stigma.

That is not to say that there are not exceptions, as is always the case in our field. For example, Alaskan Scrimshaw is often made from walrus tusk, and can maintain the shape of the whole tusk. Scrimshaw is a native art and tends to carry its own regulations. Look for a signature, check to see if the piece is fossilized, and then you may still want to reach out to an expert on the topic.

If the piece in question is worked ivory, not scrimshaw, there may be some options for the client. What kind of worked ivory might you see? Most commonly encountered are Japanese netsuke, Chinese imperial figures, Chinese toy-like pieces, Chinese export miniatures (with a more western appeal), European miniature portraits painted on ivory, Persian works of ivory, 18th and 19th century Continental and European carved boxes or miniature shelves, inlaid furniture, musical instruments and their parts (commonly the frog of a violin, viola, or cello bow), and the list goes on.

Once you identify the object then you can determine the value of the work.

How much ivory is in the piece? Is it all ivory? Where would the value of the work come from?

There are some U.S. Fish and Wildlife exemptions that are important to know, including the de minimis exception:

According to U.S. Fish and Wildlife, “The de minimis exemption applies only to items made from African elephant ivory. The African elephant 4(d) rule provides an exemption from prohibitions on selling or offering for sale in interstate and foreign commerce for certain manufactured or handcrafted items that contain a small (de minimis) amount of African elephant ivory” (Footnote 1).

This exemption would allow a client to sell an item locally, interstate, or internationally. This in turn, opens up the market one can access and research when finding comparable sales for an appraisal report. But, what exactly qualifies as di minimis? U.S. Fish and Wildlife stated:

“To qualify for the de minimis exception, manufactured or handcrafted items must meet either (i) or (ii) and all of the criteria (iii) – (vii):

(i) If the item is located within the United States, the ivory was imported into the United States prior to January 18, 1990, or was imported into the United States under a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) pre-Convention certificate with no limitation on its commercial use;

(ii) If the item is located outside the United States, the ivory was removed from the wild prior to February 26, 1976;

(iii) The ivory is a fixed or integral component or components of a larger manufactured or handcrafted item and is not in its current form the primary source of the value of the item, that is, the ivory does not account for more than 50 % of the value of the item;

(iv) The ivory is not raw;

(v) The manufactured or handcrafted item is not made wholly or primarily of ivory, that is, the ivory component or components do not account for more than 50 % of the item by volume;

(vi) The total weight of the ivory component or components is less than 200 grams; and

(vii) The item was manufactured or handcrafted before July 6, 2016.” (Footnote 2)

Let’s simplify this a bit, what do you really want to see? If the item is in the United States, import documents or receipts proving the item was in the U.S. prior to 1990 – these can be purchase receipts, previous appraisals, certificates, etc. If the client has previous import permits, these can be dated more recently as long as they prove a successful and legal import. If the piece is located outside the United States, the supporting documentation should prove that the item was made, and therefore the material taken from the wild, before 1976.

Additionally, you need to be able to show that the piece was made prior to 2016, that the ivory does not account for 50% of the value or volume, and it is less than a total of 200 grams.

The ivory portion of the piece must be integral, or cannot (at least should not) be removed from the object.

Examples of de minimis works of art include violin bows such as those made by Étienne Pajeot with an ivory inlaid frog (hand hold). The maker establishes a date range for the age and the value. The bow would likely be valued for its usability and quality because of the maker.

Another example is a large ivory inlaid chest, circa 1880 made in Philadelphia. Again, the value lies in the provenance and origin. For instance, there is a market for Philadelphia furniture from the 19th century, regardless of the inlay material.

For items that fulfill the di minimis rule, you should be able to include these in an appraisal or provide advice about selling. Sometimes, you will find comparable sales where the seller, concerned with regulations, removed the ivory from the piece. In most cases, the small amount of ivory has no bearing on the value or appeal of the object, and as the appraiser, you can make the appropriate comparisons.

The piece is all or mostly ivory and worked, what paperwork does my client have to produce?

Examine the piece with the idea that it should be legal to export internationally. When appraising an ivory work of art for fair market value, the most common marketplace would be from international sellers such as auction houses or dealers. This would often be the same marketplace to search for comparable sales.

The legal export and import of ivory, as well as other endangered species material, is regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, more commonly known as CITES (Footnote 3).

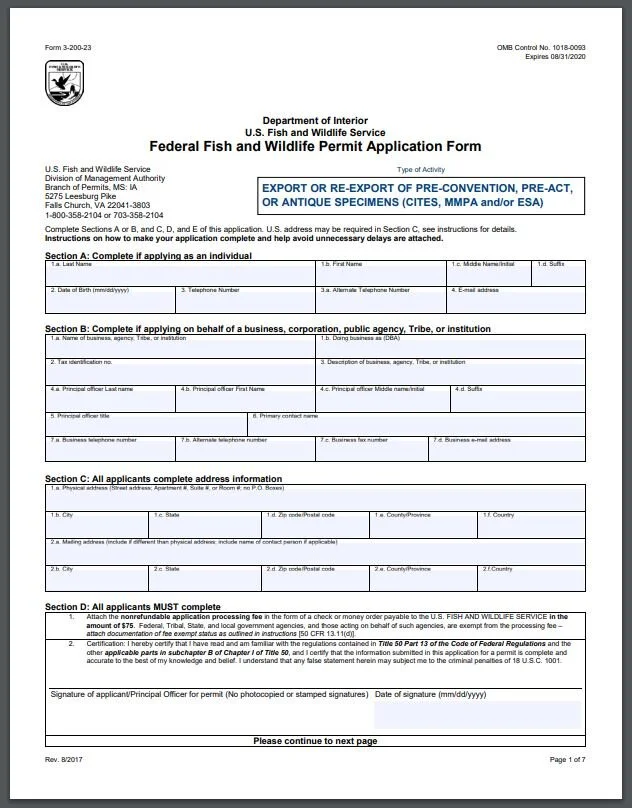

When an ivory items sells at auction or through a dealer to an international buyer, the seller will need to apply for a CITES permit for export. Before sale, it is the responsibility of the seller to gather all documentation they have on the pieces and determine which exemption will be appropriate.

1. Di Minimis (as discussed above)

2. Pre-Convention

3. Pre-Act

4. Endangered Species Act (ESA)/Antique

As an appraiser, you will likely handle ivory items that qualify as ESA/Antique. This means that the item is over 100 years old, has not been repaired with newer animal or plant material since 1973, and entered the United States before 1982 or through a designated port with proper paperwork.

Ask the following questions:

Does your client have a recent appraisal, or could an appraiser confidently say the item is over 100 years old and has not been repaired or modified with more endangered species material?

Does your client have receipts or purchase documents dating back prior to 1982? Or does your client have CITES permits from previous imports?

The more documentation or proof of age the client has, the more likely it is to be approved for export and therefore, the more likely it is to have value. If you are unable to prove that the item is over 100 years old, you can try to see if the item would qualify as pre-act or pre-convention. Pre-act means that the specimen was made or acquired before the Endangered Species act was passed in 1973.

Pre-Convention means the specimen was acquired prior to the date CITES was applied to it. In general, https://www.speciesplus.net/ is where you would determine when CITES was applied to a particular species. While it may have been listed on appendixes i, ii, or iii, you simply want to look for the earliest date the species was listed. Generally, ivory was listed as early as 1975 for import or export in any country.

I have the paperwork, I have the proof, how do I sell the piece?

The above qualifications can begin to help you understand if the item you are looking at is saleable and if you are able to find comparable sales for an appraisal report. In addition to qualifying for one of the four exemptions mentioned above, an application for export will ask for the particular species and they will also ask for an “appraisal.”

What they are looking for is an expert statement saying that the item is (1) made of the species you say it is, (2) it is as old as you say it is, and (3) it has not been modified. They are not looking for any statement of value. This expert should be a third, uninterested party, and the document should list their qualifications and expertise.

In the case of ivory, there are two primary species: African Elephant, or Loxodonta Africana, and Asian or Indian Elephant, Elephas Maximus. Regulations on Asian Elephant, particularly in Asia, are very strict and often import is banned. You can use your own expertise, research, and provenance to come to your best assumption that the piece is made from a particular species. You can also seek an expert to determine the species.

Overall, there are still state laws that prohibit sale of ivory and other materials even if you can confidently say the item is antique and can prove the value is not in the ivory, your client has all the correct paperwork, and you’ve fulfilled the federal requirements. Many states (e.g., California, New York, New Jersey) have very strict and specific rules on ivory trade. This makes items more valuable in some places than in others. Additionally, the regulations quoted here and set forth by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service are vague; however, their permit processors can be as specific as they feel necessary. No sale, shipment, or export permit is ever guaranteed.

The information in this article is for general informational purposes only and is not considered legal advice or a legal opinion. In addition, topics may not necessarily reflect the most current appraisal developments. Seek the advice of a professional knowledgeable in your region or country before acting upon any of the information included in the text above.

About the Author: Richelle Simon, ISA, is a member of the International Society of Appraisers and works with Lark Mason Associates/iGavel Auctions. She oversees incoming and outgoing consignments in the Texas office, handles all endangered species paperwork, coordinates and manages appraisals and special projects. She can be reached at richelle@larkmason.com

Additional Resources

Cited Sources:

Footnotes 1 and 2: “De-Minimis-Exception.” U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, International Affairs, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, www.fws.gov/international/travel-and-trade/de-minimis-exception.html.

Footnote 3: “CITES.” Official Web Page of the U S Fish and Wildlife Service, www.fws.gov/international/cites/.

Useful and Related Links:

https://www.fws.gov/international/cites/

https://www.fws.gov/international/travel-and-trade/de-minimis-exception.html

https://www.fws.gov/international/pdf/african-elephant-ivory-de-minimis-examples.pdf

https://www.speciesplus.net/

https://www.fws.gov/international/laws-treaties-agreements/regulations.html

https://www.fws.gov/international/travel-and-trade/questions-and-answers-esa-cites.html#11

(What will the Service accept as a qualified appraisal) https://tbamf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Ivory-Document-2017.pdf

For the latest news on Ivory regulations in the United Kingdom https://www.bada.org/news/ivory-act-supreme-court-denies-permission-further-appeal

Images List

Hair Comb Decorated with Rows of Wild Animals, ca. 3200–3100 B.C., Predynastic, Late Naqada III, Egypt, Ivory. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

Bone (unidentified) as seen through a loupe. Source: Richelle Simon, ISA

Ivory (Elephant) close up image, Schreger Lines. Source: Richelle Simon, ISA

A Scrimshaw Walrus Tusk, Probably American, 19th Century. Source: Christie’s (New York)

Netsuke, 19th century, Japan, Ivory. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

Portrait of a Gentleman. 1770, Henry Benbridge, American, Watercolor on Ivory. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

Étienne Pajeot, A Nickel-Silver and Ivory-Mounted Violin Bow, Mirecourt, Circa 1840. Source: Christie’s (New York)

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Form 3-200-23: Export or Re-Export of Pre-Convention, Pre-Act, or Antique Specimens (CITES, MMPA, or ESA), page 1. Source: https://www.fws.gov/forms/3-200-23.pdf

© Richelle Simon, ISA 2020