How to Evaluate an Unsigned or Unidentified Painting

Nearly every appraiser frequently encounters the often-dreaded category of “unsigned and illegibly signed” artwork. It can be frustrating for us to not be able to identify the artist of a painting for our client, even after extensive research in fine art databases. As an artwork’s value is traditionally established with a history of previous sales records for art by the same identified artist, these unsigned or illegible paintings unfortunately will typically have limited value in the marketplace, despite their aesthetic appeal.

While these artworks fall outside of the scope of work of many appraisal assignments and receive little professional attention, California appraiser Elizabeth Stewart, PhD is a connoisseur of unidentified art and its charms. In the following article, she shares with our readers her method for evaluating unsigned and identified art based on its composition and visual elements to help guide collectors who may be considering purchasing an unidentified painting.

I am an appraiser and have a little secret: for over thirty years, I have been collecting unsigned paintings from thrift stores. My Santa Barbara office, my house, my storage locker, and even my son’s home are full of these little treasures. Some of my clients even know this secret of mine!

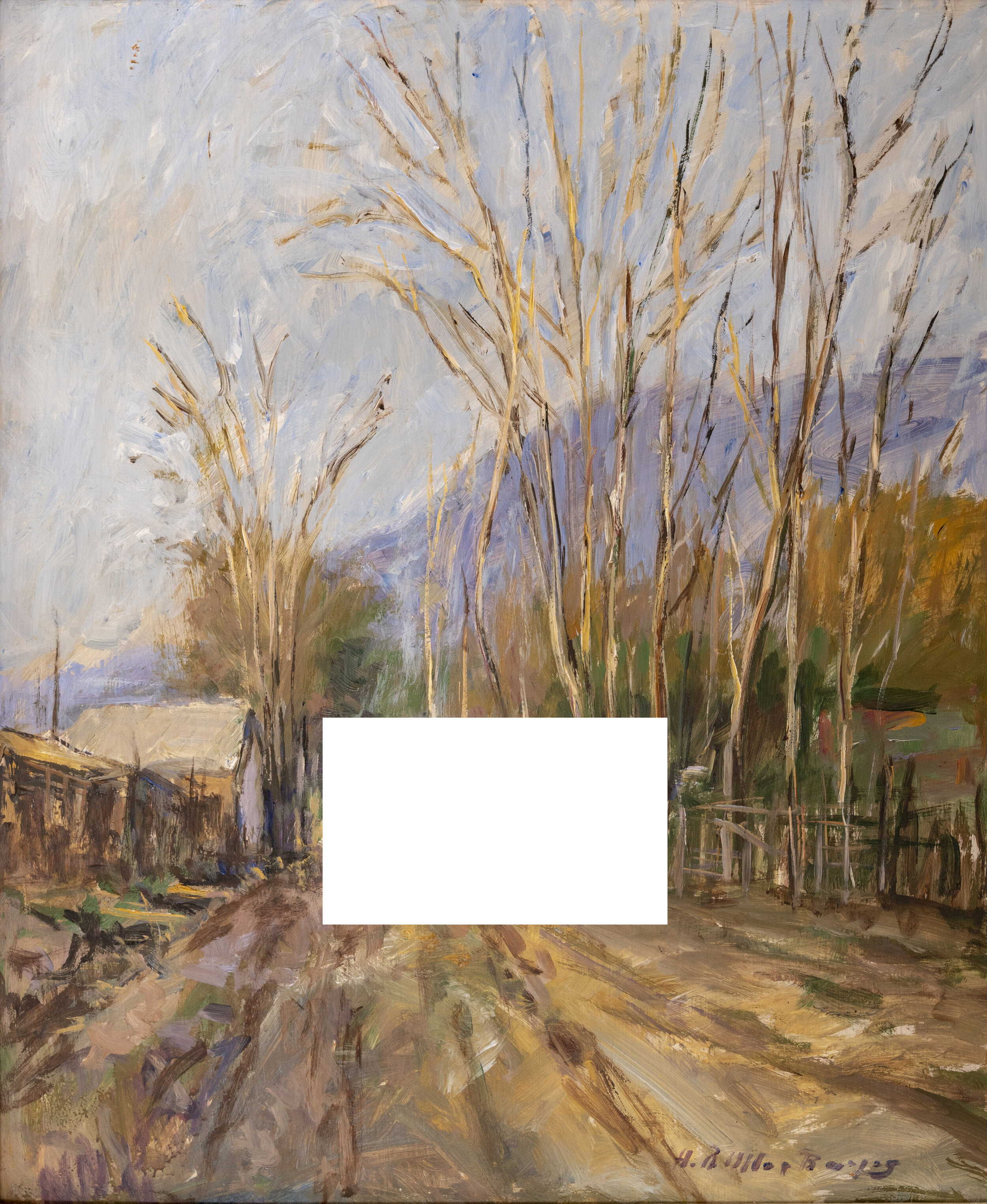

Recently, a long-time client sent me a photo of a painting at a thrift store that she was considering to purchase. She asked how I look at, and evaluate, unsigned works of art. I have a lifetime of involvement with such “orphaned” works of art that cannot be traced to a specific artist. Although I use all my powers as an appraiser of art for decades to find attribution, and sometimes I still can’t identify the style, the palette, or the origin. So, as I explained to my client, this is how I judge a work of art, taking her unsigned thrift store work of art as an example.

1. Rotate the Painting

The first thing I do is to flip a work of art 180 degrees. I turn it on its head. Then I set it down that way, and back away. I see if a work’s composition holds up in this reverse situation. If I am looking at a representational work, I squint my eyes so that I envision just the forms in a work. I tried this with the photo my client sent me (shared here with permission). The painting looks promising, and I think we should go on with this test of integrity.

The two main anchors of her chosen work are the road and the grouping of trees. They “frame” the piece. Both aide in centering other elements of the painting. These two “walls” work well for me, when viewing the work upright, and flipped over. Why do I do this?

There’s an abiding “law” in art that a GOOD work of art - whether it be a film, a painting, a poem, a novel - should contain all the elements needed to deliver a feeling, a revelation, and a message (and communicated successfully); conversely, art should include nothing extraneous. Which means that if you flip a painting upside-down, looking at just the forms, you should still be able to “read” a complete whole. In my client’s painting, the three forms in the middle of the composition hold together well. In other words, they seem to relate to each other. This is a point in favor of the work.

2. Try the Index Card Test

To determine if a work of art has artistic integrity, take one element out. I carry a 3 x 5-inch index card with me, and I use it to block out one area; for example, a highlighted element (i.e., an area very lightly colored, for example), or something central to the structure, or something very dark in the piece. If the piece falls apart like a badly constructed bridge, I think, “Good, I have just saved a little money today.” To take an integral element out, and to have the work suffer, means that the detail is totally necessary, and not just painted for the sake of the story. An example is a tightly composed portrait of an entire family in which one member of the family, if removed, should cause the whole “knitted together” composition to fall apart.

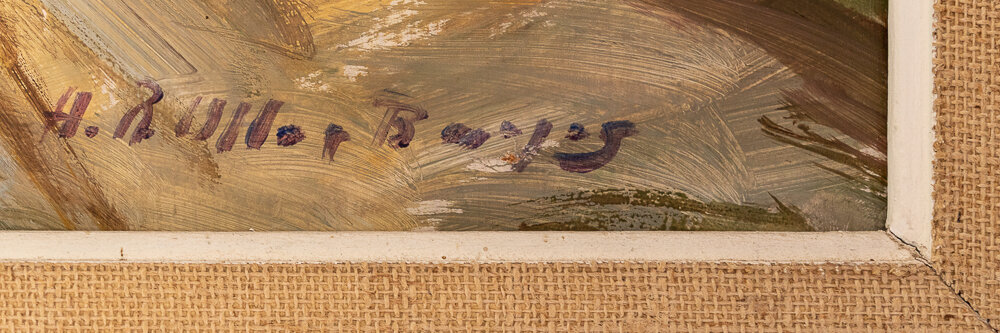

3. Look at Placement of Artist Signature

The third test of artistic integrity of a painting is rather simplistic. Look at my client’s thrift store painting: it has a signature in the bottom right corner. This sits on the compositional element of road without distracting the eye from the rest of the scene. This, to me, is a good sign. Firstly, the artist thought about the composition when he/she signed the work. That shows some talent and forethought. Secondly, most good painters have very interesting signatures. You may not be able to read them, but they do not jump out; they are artistic, and they are painted in a color that harmonizes somehow, or, for a good reason, do not harmonize. Many collectors can tell the date of a work by just the handwriting and placement of the artist’s signature. A good painter will work on a signature throughout their careers, and will place it intelligently. An amateur signature shows a lack of such care.

4. Observe the Quality of Brushwork

The fourth indication of a good painting is that the brushstrokes do flow evenly, and the colors are not muddied. An artist friend, who is also a teacher, tells his students: “The important moment is to know when to STOP painting on a particular canvas.” He goes on to say, “Because if you don’t know when to stop, you run the risk of producing the big potato in the sky.” What he means is that overwork can produce muddy colors with certain media. In oil, overwork can show in the brushstrokes, because they lose a certain freedom of movement. And an area can turn that ominous brown of overwork.

5. Get a Quick Impression

Finally, I look for the one element that makes me stay with a painting longer than five seconds. If my eye stays in the painting, I ask, “What is it that draws me in?” This one element should be related to the other elements in the composition so that your eye moves, or is directed through, the entire work. This one feature (you keep interested, and your eye moves), is common to all great works of art.

So my answer to my client? If you like the painting, and it meets three out of four criteria above, you have my blessing to spend the money! It may end up in the storage, but at least you own a visually-pleasing work of art.

Many thanks to Elizabeth Stewart, PhD, AAA, for sharing her methodology for evaluating unsigned and unidentified art. This category is often overlooked, but unsigned paintings can provide significant aesthetic appeal and enjoyment to collectors provided they are well-informed and comfortable with the limitations of their market.

Elizabeth Stewart, PhD, AAA is the owner of Elizabeth Appraisals in Santa Barbara, California and a Certified Member of the Appraisers Association of America. Visit her website at https://elizabethappraisals.com.

© Elizabeth Stewart, PhD 2020